Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd. v Netgear, Inc. et al, UPC, Court of First Instance, Munich Local Division, UPC CFI_9/2023 – on opt-in (withdrawal of opt-out), exhaustion of patent rights, and FRAND defense

By decision of 18 December 2024, the Munich Local Division of the Unified Patent Court found that three Netgear companies (Defendants) infringed the European Patent EP 3 611 989 (patent-in-suit), a patent essential for the Wi-Fi 6 standard and owned and asserted by Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. (Claimant). The Court issued a permanent injunction for Belgium, Germany, Italy, Finland, France and Sweden and ordered Defendants to inter alia give information and render accounts regarding their infringing activities, remove the infringing embodiments (so-called “Access Points”, or Wi-Fi routers) from the channels of commerce and hand them over to a Court bailiff for destruction, with the exclusion of products equipped with a Qualcomm modem placed on the EU market within a certain period.

A previous post about the decision can be read here.

Facts of the case/technical background

The object of the patent-in-suit is to improve data transmission (sending and receiving) within a Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN) in accordance with the Wi-Fi 6 standard (IEEE 802.11ax) by reducing signaling overhead. The patent-in-suit relates to a method as well as devices for transmitting and/or receiving information within a wireless local network.

Claimant had declared towards IEEE that the patent-in-suit was essential for the Wi-Fi 6 standard and issued an IEEE-LOA (Letter Of Assurance) in July 2019.

Claimant first opted-out the patent-in-suit from the UPC’s exclusive competence by application of 14 May 2023, but withdrew the opt-out by application of 24 May 2023, before filing their infringement complaint on June 1, 2023.

Defendants filed a Preliminary Objection disputing the UPC’s competence because the withdrawal of the opt-out (opt-in) was invalid and could not be repeated because of a pending national nullity action against the German part of the patent-in-suit. Furthermore, Defendants filed a counterclaim for revocation.

Decision by the Munich Local Division

In summary, the Court confirmed that it was competent to hear the case at hand and found the patent-in-suit to be infringed and valid. As a consequence, the Court dismissed Defendants’ Preliminary Objection as well as their counterclaim for revocation and issued inter alia a permanent injunction against Defendants.

Competence of the UPC (Section A., pp. 19 et seqq.)

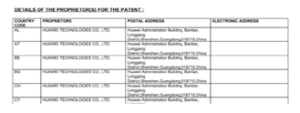

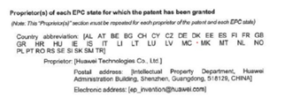

The Court confirmed the UPC’s competence because the opt-out of the patent-in-suit had been validly withdrawn. Defendants pointed to the template provided in the CMS (cf. below, as used by the Claimant for their opt-out) and argued that Claimant had violated their obligation to use such “official form” for the withdrawal of the opt-out pursuant to Rule 4.1 RoP (2nd sentence):

The template used by Claimant did include the same information, but in a different format and without repeating the Claimant’s information for each national part:

The Court found that the only official form for declaring the withdrawal of an opt-out was the corresponding CMS workflow, that the template provided in the CMS (see above) was not mandatory, because it was not an “official form” in the sense of Rule 4.1 RoP but only a “template to support”, and that, thus, Claimant was free to use a different template since they had filled out the information required by the CMS workflow correctly.

No covenant not to sue based in the IEEE-LOA Bylaws (Section B., pp. 25 et seqq.)

The Court also dismissed Defendants’ defense that the complaint was inadmissible based on a covenant not to sue in the IEEE Bylaws. Notably, such covenant not to sue was not included in the IEEE Bylaws in effect as of March 2015 (IEEE Bylaws 2007), which were incorporated to the Claimant’s LOA, but only added in later versions. In particular, the Court refuted Defendants’ argument that the IEEE Bylaws 2007 were automatically replaced by subsequent versions of 2015 or 2022, which included such covenant not to sue, because Defendants’ could not show any IEEE regulations stipulating such replacement mechanism. To the contrary, Claimant and other patentees had actively rejected the IEEE Bylaws 2015, giving a “negative LOA” in that regard.

Counterclaim for revocation (Section D., pp. 58 et seqq.)

Based on its well-reasoned interpretation of claim 1 of the patent-in-suit (Section C., pp. 28 et seqq.), the Court dismissed Defendants’ counterclaim for revocation.

In particular, the Court found that there was no inadmissible extension because the subject matter of the patent-in-suit was disclosed in the original application, and that the patent-in-suit validly claimed its priority. The Court then briefly dismissed all novelty attacks raised by Defendants, in part because of the valid priority and in part because some of Defendants’ novelty attacks were late-filed. The reasoning of the Court with regard to inventiveness is particularly interesting, because the reasoning of the decision acknowledges the different approaches taken by the UPC and by the EPO Boards of Appeal and then goes on to explain in detail, why the method according to claim 1 of the patent-in-suit was inventive over the asserted combinations of documents using both approaches.

Infringement (Section E., pp. 88 et seqq.)

The decisive battle regarding infringement took place in the field of claim construction and not in the field of the realization of the features of claim 1. Accordingly, Defendants even admitted in the oral hearing that, if the Claimant’s claim construction was applied, it could not be disputed that the Wi-Fi 6 standard made use of the patent-in-suit (p. 109).

The reasoning of the decision still explained in detail why the claim features were realized by the standard and also – because Claimant had conducted their own tests and submitted the results – by the attacked embodiments specifically.

Furthermore, the Defendants’ infringing activities were laid out, with a focus on their offering of the infringing embodiments on their respective websites, confirming direct and indirect infringement.

Exhaustion (Section F., pp. 119 et seqq.)

Regarding exhaustion, the reasoning of the decision includes some interesting principles:

a) The Court stated that exhaustion applies to method claims, concerning products which are directly obtained by a method carried out with the patentee’s consent as well as products using a method claim to the extent that they are protected by a product claim, too, and that they were put on the market with the patentee’s consent.

b) With regard to its territorial scope, the Court confirmed that products must be put on the EU market for exhaustion to apply.

c) With regard to the exception in Art. 29 UPCA (“unless there are legitimate grounds for the patent proprietor to oppose further commercialisation of the product”), the Court was doubtful whether such exception could apply at all in patent law, since it is generally acknowledged that any use restrictions in a license agreement have no influence on exhaustion; referencing the CJEU judgment in Coty Prestige v Simex Trading (decision of 3 June 2010, C-127/09), the Court stated that such legitimate grounds opposing exhaustion would at least have to be recognizable for the downstream market.

Regarding the handling of the principle of exhaustion in proceedings, the Court found that exhaustion must (only) be assessed in infringement proceedings if it concerns all attacked embodiments. If this was not the case, it should be decided on a case-by-case basis whether exhaustion is to be dealt with in the proceedings on the merits or later, during enforcement. Since exhaustion applies to individualized products and specific actions, a final review will usually only be possible during enforcement.

However, the Court can prepare such review in the infringement proceedings by answering preliminary questions, and in the case at hand, the Court did so by finding that exhaustion applied to Access Points (Wi-Fi routers) equipped with a Qualcomm modem placed on the EU market in a certain period due to a license agreement (PLA) between Huawei and Qualcomm.

FRAND defense

Regarding Defendants’ FRAND defense, the Court confirmed that the UPC will review such objection and decided not to refer any questions in the present case to the CJEU for a preliminary ruling pursuant to Article 267 TFEU.

On the substance, the Court confirmed the application of the FRAND negotiation program stipulated by the CJEU in Huawei v ZTE, namely that

a) the SEP owner must first notify the implementer about the patent infringement before filing a complaint, that

b) the implementer must indicate their willingness to take a license in reaction to such notification and that

c) both sides must then (continue to) work towards concluding a FRAND license agreement in accordance with usual business practices; more specifically, the SEP owner must make a license offer under FRAND conditions, including a specific license rate and its calculation method, and the implementer must make a counter-offer under FRAND terms and, in case such counter-offer is declined, render accounts and provide sufficient security.

In this course, the Court stated that not only the SEP owner’s first offer must be reviewed regarding its “FRANDness”, but all offers which are still open for acceptance by the implementer. Furthermore, such offer did not have to be made in its final wording with all details, ready to be signed, because its purpose was to allow the implementer to recognize the main conditions and to react, given the case, with a counter-offer.

Notably, the Court expressly declined some of the positions brought forward by the European Commission in their amicus curiae letters of 15 April 2024 to the Higher Regional Court of Munich (020078-24 MLO / DLF), confirming the recent decision of 22 November 2024 by the Mannheim Local Division (UPC_CFI_210/2023).

Applying these principles to the case at hand, the Court dismissed Defendants’ FRAND defense, in particular because they had delayed negotiations and did not provide a security or render accounts after their counter-offer was declined, and because they did not make any statements regarding the SISVEL pool license offered by Claimant in addition to their bilateral license offer. Notably, the Court also found that Defendants had not even shown that the patent-in-suit conveyed a dominant position on the relevant market to the Claimant.

IEEE LOA defense

Apart from the FRAND defense, Defendants raised a defense based on the Letter Of Assurance provided by Claimant to the IEEE (IEEE-LOA), arguing that they had a claim for a license to the patent-in-suit “under reasonable rates” and “with reasonable terms and conditions that are demonstrably free of unfair discrimination”.

The Court pointed to its explanations regarding the FRAND defense and found that Defendants had not fulfilled their burden of substantiation and proof, because they failed to show why the obligations under the IEEE LOA could not be fulfilled by offering a pool license and, in addition to that, why the offered Sisvel pool license was unreasonable and constituted an unfair discrimination.

Take aways:

In summary, the present decision provides practical assistance (opt-in template) as well as important guidelines on the handling of the principle of exhaustion in infringement and enforcement proceedings, and on the FRAND dance to be performed by SEP owner and implementer – not to forget the IEEE LOA “waltz”.